CR 009: Evan Frankfort on Music, Creativity, and AI’s Inevitable Impact

The Emmy Award-winning composer and musician discusses his storied career, his collaborations with Liz Phair, and his passion for innovation.

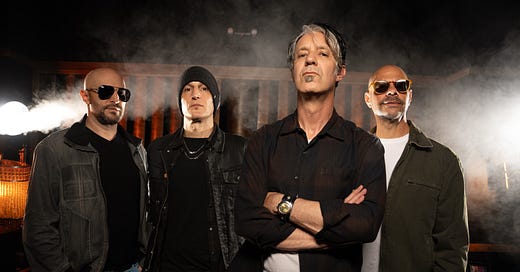

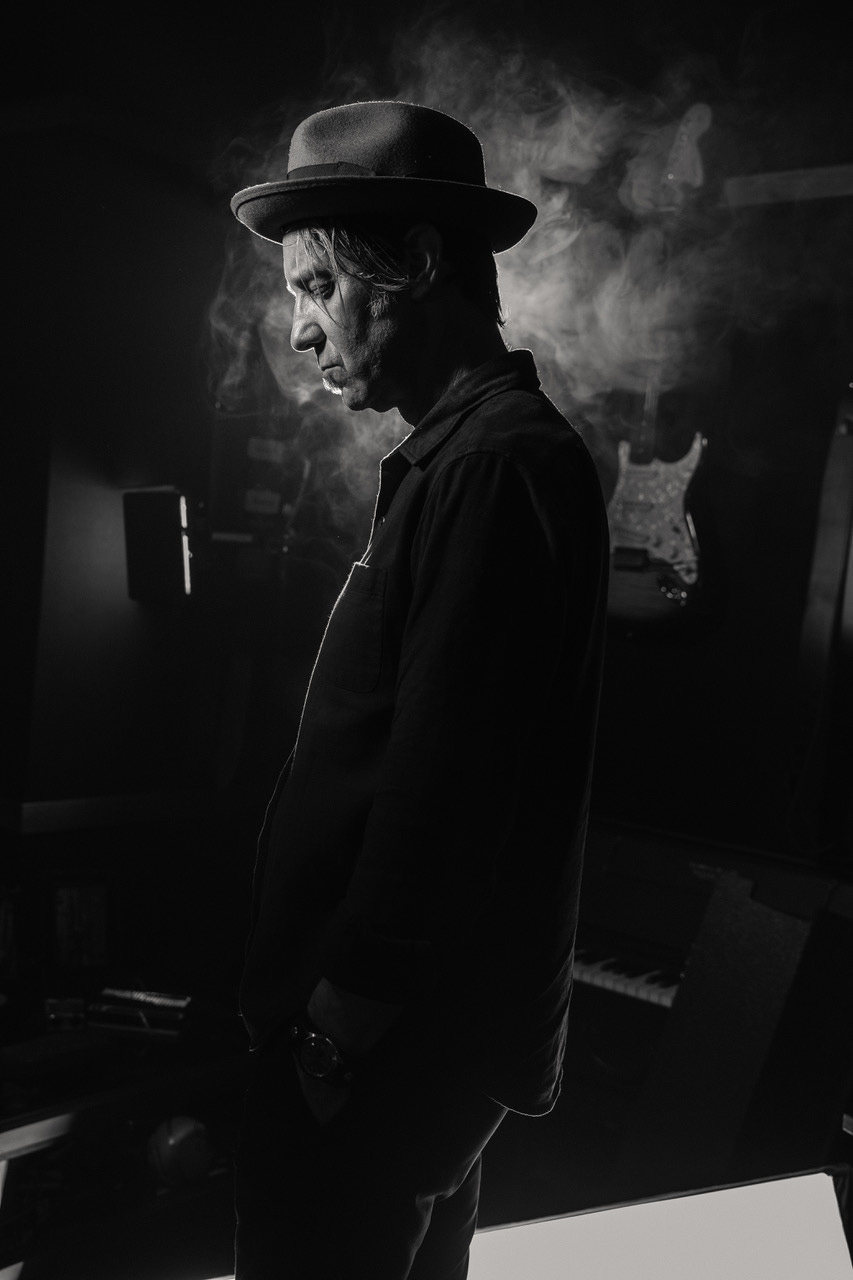

Evan Frankfort loves music. Over the past 30 years, the seasoned musician has built an impressive portfolio of work. As a composer, he’s provided the score for dozens of television shows, including The 100, Swingtown, and 90210, earning a Daytime Emmy Award (for Guiding Light) and a BMI TV Music Award (for Rules of Engagement) along the way. Through his role as Head of Music for Hearst Media Production Group, he oversees the music for 25 educational series, including Mission Unstoppable and Wildlife Nation with Jeff Corwin. As an engineer, sound designer, and songwriter, he has collaborated with numerous artists, including the Bangles, Rancid, and Liz Phair. And as a performer, he explores creativity through his bands, the Spiritual Machines and Les Friction.

To put it simply, music is just something Frankfort must do. “I can never see myself retiring,” he says. “I could never see myself being over it. I mean, it may not always be music, but it’ll always be music with whatever else it is.”

In advance of the Spiritual Machines’ upcoming LP, Lockhearted, due out on August 16th, I chatted with Frankfort about his upbringing, his process as a composer, and how he envisions a future with AI.

SANDRA EBEJER: Your website bio says that you’re a sixth-generation Angelino from a family of classically trained musicians. Can you share a bit about your background?

EVAN FRANKFORT: Let me start here: my grandfather and his [siblings] lived in Montana. Their dad was the attorney general of Montana. And in the middle of the night, they had to move because Dad did something bad. Dad was going to go to jail or something. I don’t even know what it was. But they moved to Seattle. [My grandfather and his brother] hated it. They responded to an ad for a cruise ship needing a band. Neither of them played instruments, but they saw this print ad somewhere and they called on a payphone—“Yeah, we got a band.” [Laughs] They bullshitted their way into getting this gig. They scrambled, put a band together. My grandfather learned how to play saxophone; his brother learned how to play drums. They got the hell out of dodge, where they hated it, and they lived a life of adventure. They pulled it off. None were the wiser.

My grandmother was a musician. She came from Russia at the age of three, just dirt poor. She played violin from the time that she was born. She had that four-foot, tough, Russian disposition, where she was going to dominate everyone and everything. And she had absolute perfect pitch. It’s a blessing and a curse because she couldn’t really listen to music. I remember when I was little, we were listening to a philharmonic performance of Beethoven’s Fifth and she was cringing. I’m like, “What are you doing? This is amazing.” She said, “They’re playing it wrong! It’s a triplet. The conductor doesn’t know how to lead the orchestra.” That’s the way it was for most music for her.

There are two kinds of musicians: there are technicians who play instruments, and they’re like surgeons or plumbers or electricians, and the more you practice, the better you get. That’s her world, [whereas] I’m a creative. If you give me paint or blocks, I’m going to make something. She didn’t understand that. Most musicians that are technical musicians, if you take the page away from them, they have no idea what to do. Where in jazz, it’s the total opposite; like, please take the page away so you can let my wings span.

I grew up around the corner from them. They were fascinating people and I was shaped and molded by them, mainly in terms of tenacity. I’m just gonna be who I am.

You’ve provided the score for many television shows. What is the process like when you’re working on a series?

You try to start with a clean slate, where you watch a show, you look at how it’s shot, you look at how people perform, what their rhythm is, and what their flow looks like. And you try to get with that, where you just play music, you listen to the sounds, and you get a feel for who these characters are and how they carry themselves. You’re really trying to be a natural extension of that and you’re trying to heighten whatever they’re going through, whether it’s happy, sad, whatever. And then you have to choose moments. You have to say, “Some of this stuff works better dry and if I step on it with music I’m only doing a disservice to it.”

You have this conversation called spotting. In TV it’s usually with a showrunner; in film, it’s with a director. Usually editors are very creative, and they’ve done a good job temping the score. In other words, they’ll use music from wherever that helps point to a direction. Most composers will tell you temping is their worst enemy because you get locked into whatever somebody has done. But the interesting thing about scoring is that there’s a million ways to do it well. You might have a perfect lock on the way that you approached it, and everybody will agree, like, “You nailed it. That’s amazing! Did you ever think of doing the opposite of that?”

This is where it gets fun to be a creative and not a technician. Because a technician will say, “Do you realize how perfect my performance was and how it emotes? What I did can’t be redone. It was lightning in a bottle.” A creative is like, “What other stones can we turn over? How can we fuck this thing up? How can we turn it over on its head and find a new way to approach this and give it another personality?”

You’ll do a lot of work in the beginning. Then once you hit your stride and everybody knows what the marching orders are, it usually goes quickly. On a show I did called The 100, it was literally 500 tracks of music. I had sometimes two days to write a 42-minute score, record it, and deliver it. It’s brutal under any context. I worked alone. It’s really, really hard to do something like that. Fortunately, I don’t do stuff like that anymore because it doesn’t put anybody’s best foot forward. All you do is struggle. I was very proud of what I did on that show, but 18 hours a day, seven days a week is not sustainable.

Are there types of shows that are more appealing to you creatively?

I love what I’m doing right now [Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom: Protecting the Wild] because it’s something I can be proud of showing my kids. It’s something that feels good at the end of the day. Like, we didn’t just kill kids on this show for shock value. That became the thing—if you didn’t kill a kid, then your show’s not done yet. For me, I like to connect with things that are tearjerkers and heartwarming and that inspire. Because life is hard enough. I’m not trying to add any more weight to people’s lives. I want to somehow help people through it.

You’ve collaborated on several projects with Liz Phair. How did you come to work with her?

She came in with a friend of hers. They had co-written a song called “Satisfied” and they wanted to finish it together. I helped finish the song. I produced it and played it, and it ended up on her record. And then she said, “I’ve been through so many different producers and haven’t really found anybody I like working with, but I liked working together. Can we finish this together?” So we did. That was a lot of fun.

She had a friend, Mike Kelley, who did The O.C., and he and Alan Poul, who came from Six Feet Under, had a new show called Swingtown. It was a CBS show. And doing the score was—I mean, that’s where I really became addicted to it. It was so fun, and the show was so good. I loved everything about it. Unfortunately, it got canceled. It was a little racy for CBS. But it lit the match that lit the forest fire, and Liz and I did a bunch of shows together.

She’s this very stream of consciousness type. She’s a real artist. She thinks in art terms where she’ll close her eyes and, Picasso-style, put her fingers down and go, “I like these two notes of what I just did. I’m going to move this finger here and that finger there and now I’ve got a new chord no one’s heard before.” I learned a lot from her about it being okay not to be a technically amazing musician, because my whole life was failing at practicing. I will never be a virtuoso. I just don’t have the dexterity that a lot of these people have. I’m not going to be Eddie Van Halen, as much as I love him. I just don’t have that. You can only win at being the best you.

Who are some of your influences?

As a musician early on, it was Peter Gabriel and Pink Floyd and the Who. It’s always been about storytelling. So, like everyone, [influences include] the Beatles and the Stones and the Beach Boys, but there are so many bands today: Dominic Fike, Tim and Paula, the Japanese House. These are people that young people introduced me to and they’re just blowing my mind. You have playing, you have writing, you have a sound that you’ve never heard before—or you have and you’re like, “I haven’t heard it like that before.” And there’s a fearlessness. There’s a gutsiness.

I think for so long everybody had to stay in their lane. I remember when the Wallflowers turned in the most adventurous record they ever did. It was right after Bringing Down the Horse. They worked with a producer, Julian Raymond, and they did total out of the box stuff. It was so cool and new and exciting. And the label’s like, “Nah. We just want Bringing Down the Horse part two.” You get that one song that hit and you gotta go remake it for the rest of your life.

On the Spiritual Machines’ website, it says that the throughline of your upcoming album, Lockhearted, embraces the idea behind the book The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence. What are your thoughts on AI, particularly as it relates to music and creativity?

I think we have to look at it as a partner and a tool. Right now, here’s what I see. AI is coming for all of our jobs. Let’s not confuse matters. But I think certain people feel they’re immune. They feel like, “I’m above that. I’m a producer, so I can utilize AI to eliminate singers, bands, songwriters. I can just say, ‘Here’s what I want to produce.’ And then I’m going to put it on Spotify, and I’m going to be rich.” I think that’s how people are thinking. “I’m making TV shows. All I have to do is say, ‘Computer, make me 100 shows today,’ and I’m going to deliver them to Netflix.” It’s so short sighted because all Netflix or Spotify has to do is say, “Computer, make me 100 shows today. Make them great.” And they don’t need anyone. The only survivors are the ones that have platforms. The first people to go are lawyers, because it’s book knowledge. Lawyers know this and they’re going to self-preserve.

Look, it could get worse before it gets better. It could get very bad. But I do feel like it’s going to get better, because we are all in the same boat. And we’re going to find out really quick that we have to stick together, we need solidarity. So that’s my takeaway from all of it.

But let’s face it, people don’t care. They think they do. But when I hear a great song and I’m like, “This is really moving me,” I’m not going to ask if it’s human. If I see a movie and I say, “This is the coolest movie I’ve ever seen—” Already, I’m seeing things where I know it’s AI, but it’s different from anything I’ve seen, so I’m curious about it. I’m interested in it. It’s a brand-new media. I don’t know what to make of it yet.

I used AI for my record cover. My son and I did it. We used Midjourney and we spent weeks on it. By the time we were done, we probably could have just made something by hand, but the process was really fun of refining [the image]. And then I have a real friend, a human friend, who is an amazing artist who took it and said, “This is weird. Let me fix that. And that’s weird. Let me fix that.” Then I have another friend who did color treatments and so on. It was a partnership. We had a relationship with a computer. There’s no way [otherwise] we would have gotten what we got.

The playing field is more level now than ever, and it is more about ideas than it ever has been, which is good. But then there’s also human expression and you want that to be a component in what you’re doing. I don’t think we’ll ever get away from humanity.

Do you ever get creatively stuck? And how do you break through it?

I get creatively stuck after I finish any project. That’s because you left it all on the field and so you feel like, “Well, I might never do anything again.” And then you hear a record, and you’re like, “That’s so cool. I want to go make a record like that!” And you start playing. [Or] you read a book. For me, it’s a lot of theoretical physics. I’m really into people that write about where the world’s going, Michio Kaku and Robert Lanza. I don’t take them all seriously. I’m not a real scientist, so I’ll let other people who do that poke holes. But for science fiction and for the concept of storytelling, that’s fodder for me. So watching movies, reading books, listening to records is what ignites the fire for me.

Any advice for those who want to enter the music field professionally?

Find the thing that gets you out of bed in the morning. I worked in a million different jobs. I worked as a bank teller. I was in new accounts at Great Western. I was 17 when I got hired. But I was happy. Every day, at the end of the day, I would go and work on music.

You have to have two buckets. One is, I do this because it’s work and I’m at peace with whatever it ends up being. But then you have this other bucket, which for me is Spiritual Machines, Les Friction, and the other projects that I do. They’re all monikers so that I can tell a story. One is about time-space dimension travel, Spiritual Machines is about technology and how it impacts humanity. And it’s okay if they fail. I don’t need them to be successful.

If I’m talking to somebody who’s just getting into the business now, I’m going to tell them, this is your legacy. It’s the things that you make. When you’re 80, hopefully there will be a pile of records in your corner that you can say, “I was a part of those.” And, I mean, if you can find a job that doesn’t make you miserable, you basically won at the game. If I was still at the bank, I know it would be a good life for me. I would still have this pile of records and projects. It’s about loving it and doing it your whole life.

To learn more about Evan Frankfort, find him on Instagram.

To learn more about the Spiritual Machines, visit the band’s website.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…