CR 022: Bruce Eric Kaplan on Finding Gratitude in Development Hell

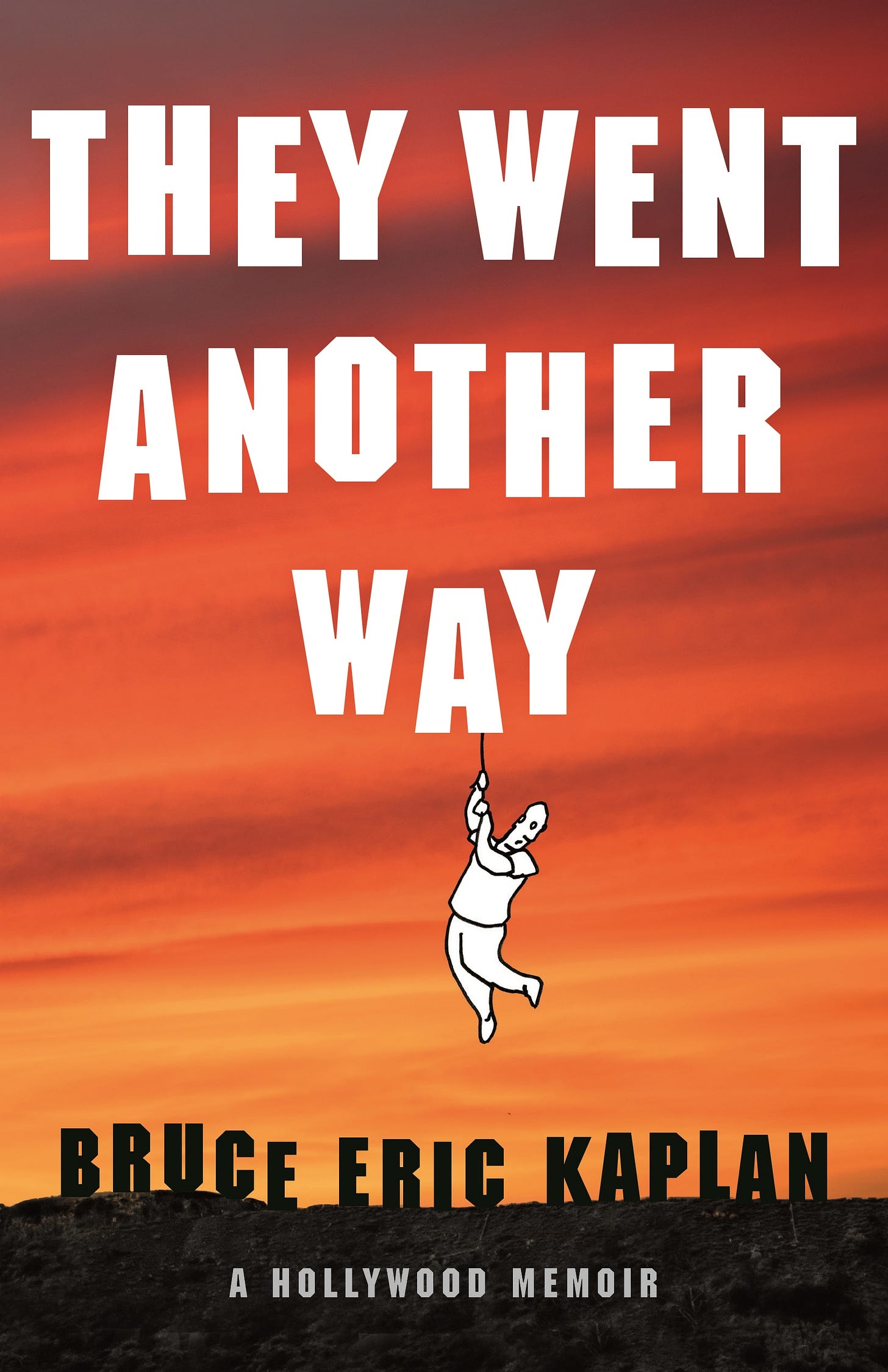

The television writer-producer discusses his return to cartooning, gaining clarity through journaling, and his new book, “They Went Another Way.”

Bruce Eric Kaplan is no stranger to the entertainment industry. A longtime cartoonist for The New Yorker, Kaplan also worked as a writer on Seinfeld and was an executive producer on HBO’s Girls and Six Feet Under. Still, nothing could have prepared him for the events of 2022. On hiatus from cartooning, Kaplan was spending much of his time trying to get a slate of projects off the ground, one of which was a May-December romance he’d written for the small screen. Glenn Close was interested in the project, as was Pete Davidson. Many, many meetings with executives were held over Zoom, yet the project seemed to be perpetually stuck in neutral. It was, Kaplan says now, different from past professional experiences. “When I started doing this a million years ago, there were three networks,” Kaplan says. “You had an idea. Your agent set up meetings, say, on Thursday and Friday, with the three networks. You went to them; you pitched an idea. You found out at the end of the day Friday if one, all, none wanted the idea. It was 48 hours of your life. Then there’s today, which is not 48 hours. It’s like this endless slog.”

To maintain some semblance of sanity, Kaplan kept a journal from January through July 2022, in which he described every maddening step of the television pitch process, while also writing his way through his anxieties around the state of the world. Published as They Went Another Way, the book is a poignant, funny, infuriating peek into a period in Kaplan’s life as well as the world at large—a period made all the more frustrating when the project that Kaplan worked so hard to bring to fruition falls apart.

Still, as he shared with me over a recent Zoom call, the project was life-changing in ways he didn’t anticipate. “The book taught me a lot about having gratitude for what I have,” he says. During our interview, we discussed his passion for writing, his love for great television, and his advice to aspiring entertainment professionals.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: How did this book come about? Did you start a journal knowing you were going to publish it? Or did the publishing aspect come later?

BRUCE ERIC KAPLAN: You never know that it’s going to be published. [Laughs] From the beginning I thought, “I want to document my life. I want to make a document of what it is to be a person in 2022.” And it’s specific to me, obviously, because it’s about my work life. But, as you know, a lot of it is not about my work life. It’s about my family and it’s about Ukraine and Roe v. Wade and MAGA. I said, “I want a document of this time.” It was a journal, but I was mindful of what was put in the journal, meaning that it was by design, so it was meant for publication, ideally.

In the book, as you just mentioned, you write about your journey of trying to get a few television projects off the ground. Now that some time has passed, what comes to mind when you look back on everything that happened—or didn’t happen—for you professionally during that time period?

I don’t look back. And sadly, because of this book, I’m forced to look back. [Laughs] I can’t believe I did this to myself, because I’m not someone who looks back. I feel, and I say this in the book when I’m talking to my friend Gary: “Everything leads to something else.” So when I think about the book and things that happened or didn’t happen, I feel like it all led to where I am in this moment, which is great. I know the person in the book is freaking out [laughs] and it seems so important, like, “Oh my god, I have to have this meeting. I have to have a show. I don’t have a show.” But I’m not in my right mind when I’m thinking that way, because the only thing that’s real is what’s happening now. The only thing that’s real is this meeting, you and I, right now. That’s it. That’s my reality. Obviously, other people have said this, but it’s true, and you forget it. I forget that, and I’m continually being reminded of that. So the short answer is, when I think about the book, it’s amazing, because it led me to this conversation right here.

In the book you write, “I thought that this journal was about me trying to get a television show bought and made. But what if it’s the opposite? Maybe this journal is about learning to stop hitting my head against a wall. Maybe it is about me finding a new life doing something completely different that I love.” What did the journal and this whole process end up doing for you? Did you find clarity as a result of working on it?

I was losing perspective at the time that I wrote this. I mean, somewhat losing perspective at times, because at times in the book I don’t. Like when I’m in the sculpture garden [at UCLA] and I realize, “This is what life is about: beauty and magic and hope and excitement and energy.” The book did teach me to remember that “if I don’t have z, then everything’s going to be bad” [is] not a good place to be. Again, bringing us back to this moment—this is all that’s real. Whatever is in the future isn’t real. That’s something else, so just focus on this. And this is great. I have a lot of gratitude.

What do you love most about your job? When do you find yourself really enjoying it?

I love the actual job. I don’t love the pitching or meetings. I don’t love all the things I have to do to get to what I love to do, which is write. When I’m writing, I feel like I’ve gone away to the most interesting place with the most interesting people. It’s the greatest feeling. I used to be, by the way, one of those writers who hated writing. It took me a long time to get to this place of loving it. It took work. I used to literally, in my 20s, crawl under my desk and cry or moan when I had to write something. When I started this journey, my least favorite part was the actual writing, and now my favorite part is the writing.

How did you get from hating it to loving it? What changed for you?

Well, I had therapy. There was an army of therapists involved. [Laughs] I had a lot of voices in my head from childhood [saying], “I wasn’t meant to do this. I don’t have a right to do this. What if it’s awful?” Just a lot of negative voices in my head. It was a process to remove them. It’s not about whether things are good or bad, it’s about being true to whatever I want to say or think or whatever the characters want. It was a process. It was at least a decade, if not longer, to let the characters talk to me. And once they did [it was] the greatest feeling in the world.

There’s a pretty big cast of characters in this book. Your agents and your manager are mentioned frequently. Have they read it? What was their response to it?

When my agents and manager told me that the project wasn’t officially over—the Glenn and Pete project—I said, “Well, guess what, guys? I’ve written a book.” [Laughs] I sent it to them, and I think they were all taken aback. That’s the best way to put it. I understand it. I don’t not understand being taken aback. I put in emails, I put in texts, I put in conversations. It wasn’t anyone’s desire for me to do this. It was a very fair reaction.

They all read it. Anyone who’s in my life had read the book and I adjusted some things so that they were comfortable with it. I wanted to be respectful of people. I think, personally, that I’m the one who’s the most exposed in this thing, but I understand that it was my choice to be exposed. It really wasn’t their choice. So it was a very tricky situation to navigate, but I think all the people who are in my life who are in the book seem to be happy with the book.

Speaking of the Glenn and Pete project, there’s a moment in the book where Glenn gives you notes on the project and they’re wildly different than what you’ve envisioned for the show. How do you deal with feedback and notes, particularly when you know that the feedback you’re getting is not great?

To be honest, each one is different for me. I don’t have a stock answer. In that one, it was just to listen. I say in the book, I’m listening and I’m absorbing it. It’s just, “Okay, these are your thoughts. Let me sit with them. Let me see what these thoughts lead to.” To give a broad answer beyond that one instance, you can get notes that you disagree with, and it can go a variety of ways. I’ve had times when the project dies after that meeting, or I have times where it stimulates thought to go in a different direction. And what is that direction? It’s not the direction I thought of, let me see where it goes. But in my experience, the most useful thing to do is just listen. Not to say, “No, but it should be this way. But no, this is the reason I did this. But no, I want to do X.” Just listen and see where it goes.

You grew up loving television. Has learning how the sausage is made, so to speak, made the act of watching TV less enjoyable?

Only if I’m not fully in what I’m watching. Baby Reindeer was—I wasn’t even going to watch Baby Reindeer. I felt like, “I can’t watch this. There’s no way I can watch this.” But then I watched it, and I was really absorbed in it. I was wrapped in the storytelling. Nothing else was happening. If I’m watching something and it’s not the greatest thing, in my opinion, of all time, then I [see] the sausage, or whatever the expression is. I’m still a kid watching something if I’m fully engaged, but if I’m not, then I start thinking, “Oh, they did this because of that. Oh, they should have done this here. This location wasn’t right.” I’ll start [critiquing] more like as a producer than as a writer.

In the book, you mention some shows that you are not a fan of. What are you enjoying right now? Who are some writers in the industry that you think are doing great work?

This is embarrassing because I’m gonna say things that I’m working on. [Laughs] I just worked on Lena Dunham’s new show [Too Much] for Netflix. Lena is always interesting to me. I worked on Girls, and I think Lena is always going to be an interesting writer and creator. Right now, I’m working on the second season of Nobody Wants This. It’s a Netflix show created by a woman named Erin Foster. I’m really enjoying working with her and I love the show. As I say in the book, I’m pretty mainstream. I still watch Sex and the City on the airplane when I’m going back and forth. I worked on Seinfeld, but I’ve always loved Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm. I have a lot of things that I go back to.

I love that you gave a shout out to The Monkees in the book. I was a huge fan of that show.

It was so unusual, wasn’t it? I know it’s influenced by A Hard Day’s Night, which I actually don’t love. I prefer The Monkees. I love anything that’s surprising. The Monkees was very surprising. You never knew what was going to happen on a Monkees episode.

I want to ask about your cartooning. Most writers say that they write to learn more about themselves or to work through a problem. Do you find that cartooning allows you to do that?

Oh, yeah, big time. For decades, the cartoons were my journals. I would sit down at the drawing table and work out whatever was going on in my head. Not that I always knew what was going on in my head, but if I was mad at someone, if I was upset about something, it would come out in a cartoon.

You write in the book that you’d stopped cartooning for a couple of years. Why did you stop?

I don’t know. I don’t have a reason. It was a variety of things. I just was like, “I don’t know if I want to keep doing this.” I think 2016 was a real turning point for me, specifically the summer of 2016. I was reading about the rallies for Trump, and I felt like, “Wow, this seems really weird, these rallies. Doesn’t seem like a normal thing.” Traditionally, I read the newspaper; I don’t watch TV news. But there was a night in the summer of 2016 where [a Trump rally was] on CNN. I was like, “What the hell is going on?” When I saw what was happening at these rallies... I started meditating the next morning. [Laughs] I think that was an element to stopping the cartoons. I stopped in 2020, actually, with the pandemic. I started just drawing in the pandemic without cartoons. I would do drawings like this [holds up a drawing of buildings]—no people, just buildings. I did maybe 3,000 of those drawings during the pandemic. So, it was the pandemic, it was 2016—not that I stopped in 2016 because it was four years later that I stopped. But I sort of lost a piece of myself, I guess. And it was a journey back to rediscovering that part of myself.

What advice would you give to someone who aspires to work in the entertainment industry?

I don’t know what it’s like to start out in 2024, because I started out in another century. But I still believe this is true, based on people I work with currently who are young. I would say, “Take anything; do anything.” Be an assistant, work at an agency, work for a publicist, work somewhere, and then get from that job to the next job, to the next job. Even as a writer, it was helpful for me. I had day jobs, and the day jobs were helpful to get me to where I would go. Someone recently said their son didn’t want to take a job because it didn’t interest him or something like that, because he wants to be a creative person, and I was like, “I think he should take a job, and it’ll lead to something else.” That’s all I would say.

What do you want readers to get from this book?

Well, two reactions to the book were very meaningful to me. One was a stranger who read the book. He said, “I finished your book, and it made me want to call my mother.” [Laughs] That was really meaningful. I felt like he really understood, because for me, the book is about remembering what’s important and who’s important in your life. And then another [person], someone who’s an old friend who’s in the book, said, “I finished your book, and I was in my kitchen enjoying my blueberries. I was enjoying eating my blueberries like I had never enjoyed eating blueberries before.” That was very meaningful to me. She said, “It’s because of your book that I was able to enjoy my blueberries this morning.” That’s what I would want from someone reading the book.

Now that this book is coming out, what’s next for you?

I’m still finishing up work on this Lena Dunham show, just giving notes on cuts for episodes, and I’m in the writer’s room on the second season of Nobody Wants This. That’s the immediate thing. Doing cartoons in my spare time and panicking about the election in November. You know, just living life.

To learn more about Bruce Eric Kaplan, find him on Instagram.

To purchase They Went Another Way, click here.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…