CR 018: Artist TB Ward on Going Back to Basics

The artist-musician discusses his upcoming gallery show, his creative process, and his return to old-school techniques.

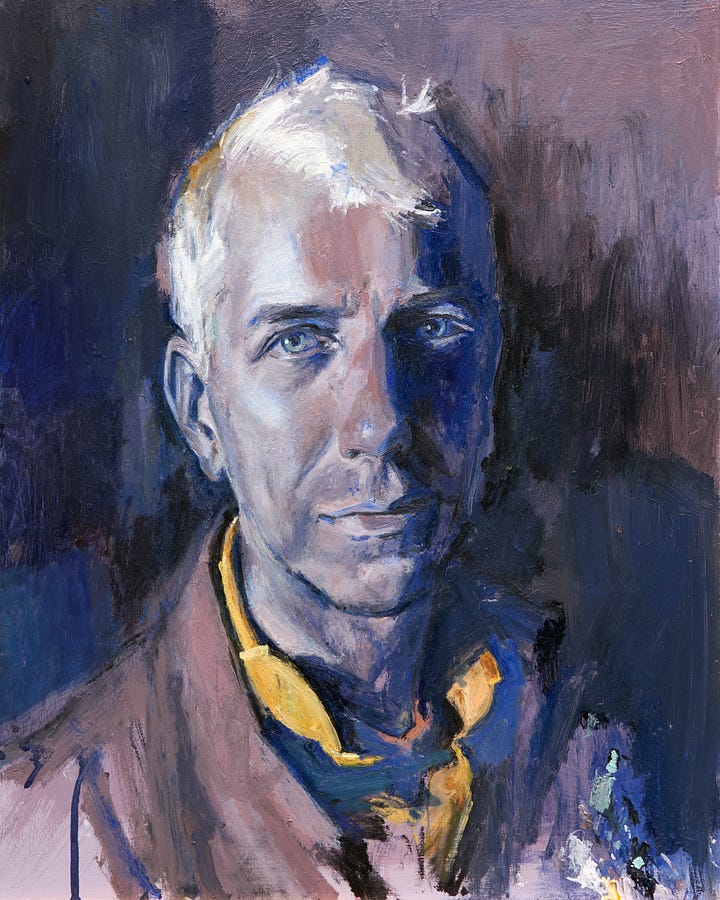

English-born, New York-based artist TB Ward has worked in a variety of mediums over the course of his career. After spending much of the ’90s as the frontman for the British indie band Elevate, he moved to the U.S. and rediscovered his love for visual art. Over the past two decades, his abstract paintings and mixed-media installations have been exhibited in numerous galleries. But in recent years, he’s found himself drawn to the classic art form of portraiture, and in October will exhibit seven oil paintings at a solo show at Upstream Gallery in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

Titled Professional Human, the show, which runs from October 3rd through 27th, is Ward’s “reaction to the idea of a ‘personal brand’ and the fictional world people create online,” according to the artist’s statement. To enhance the gallery experience, he’s put together an aural accompaniment of original music and songs, which he recorded using a 4-track cassette recorder. Combined, the music and portraits have provided Ward with an opportunity to create art in an analog fashion—a perfect counterpoint to our overly filtered, social media-obsessed world. It’s a process he says he’s come to really enjoy. “It’s taken me months to do these paintings,” he says, “but I started to really like that. I was so immersed in making these paintings and spending longer on them than previously that it seemed like the opposite of selling yourself and posting what you’re having for breakfast on Instagram.”

The songs and stories will be released digitally and will also be available as a limited-edition vinyl LP at the show. As an added bonus, Ward will perform the songs live at the gallery on October 26th. As someone recently pointed out to him, the music adds an interesting new component to the exhibit. “I had these guys come up and we were talking in my studio,” Ward says. “One of the guys was like, ‘You’re doing portrait painting and music, and then on the record, there’s short stories. It’s almost like the whole show is a portrait of you.’ I was like, ‘Oh, that’s nicely put. Wish I’d thought of that!’”

Over a recent Zoom call, Ward and I discussed his impressive career, his influences, and letting go of external validation.

SANDRA EBEJER: You grew up in a rural area of England. How did your journey as an artist begin? Did you know from a young age that this is what you wanted to do?

TB WARD: I don’t know if I ever had that level of clarity of thought. I was always really into it. I would pore through art books my parents had, and I started drawing at a pretty early age. I loved art classes when I was at school, so it was something I knew I was going to carry on doing. I just kept going to the point where I got into college, and then my parents sit me down and say, “You sure that fine art is what you want to do?” I mean, they weren’t trying to push me in any direction, but I think they wanted to make me aware that it wasn’t the most straightforward of career choices.

How did you transition from visual art to music?

I went to college, and I did the first two years. First year was great; second year, not so great. I managed to fail the second year. I didn’t get on with the tutors particularly well. I was immature. So I failed that year, and then I was going to transfer to a different college. I had some interviews to redo my second year somewhere else and I was like, “These people are exactly the same as the people who just appeared to not really like me.” So I thought, I’ll take a year off. I ended up going home and living with my mum and dad, and during that time, I met up with two friends who were also kicking around in this strange post-student time. They both played guitar. We started recording for a bit of fun, really, but I think we straight away knew that it was quite good. I look at it now, and I think it’s weird that we totally committed to this thing, even though there was no real reason to do it. I started playing guitar in the band, but in the first gigs, I could barely play a chord. I learned on the spot. That was 1991 and we ended up doing that band until ’99 when I moved [to the U.S.]. So, quite a long time.

And you transitioned from that back to visual art?

I never dropped the art completely. I made the artwork for the albums and posters and stuff like that, so I was always carrying on with the visual art. When I came over [to the U.S.], I didn’t know anybody. Me and my wife, Ruth, got married in ’98. The reason we moved here is because she got a job, and I was ready for a change. So we came over and I started painting [to do] something familiar. But once I got back into it, I never stopped. Because people start seeing what you’re doing and liking it. It gives you a little bit of a boost. So I started making more and more from that point.

You’ve moved back and forth a few times between the U.K. and the U.S. How does the setting in which you reside impact your work?

I think about this quite a bit, because a lot of [artists] tend to have a style and they do what they do. I feel like I’m always flitting around. I know that when I’m in a rural place, I immediately start going for the sketchbook and start drawing stuff. When I moved back to England in 2014, my dad was quite ill. I moved back to the little town where I grew up and I tried to carry on making my weird abstract wire paintings. A friend of my family’s gave me the corner of his barn. I’d go there and work every day. But there’s nothing really going on. I thought, I could be making amazing stuff here and literally, nobody cares. There’s nowhere to show it. So that’s when I was like, okay, I’m gonna start painting. I’m gonna go out and sit in the field and pretend to be Vincent. I always wanted to do that; I’m generally not organized enough to get around to that sort of thing. I had time, and I was like, well, I might as well experiment and try and get better at painting. I wouldn’t have done that if we didn’t come back to that spot.

The idea behind your upcoming show, Professional Human, is interesting. What made you decide to explore the topic of a personal brand?

Everything’s born of lots of different ideas, and some of it is that, yeah, I’m not that comfortable with selling myself. Also, making abstract paintings, you can start believing your own hype because you’re living in your own world. You’re in your studio and you’re making these paintings, and you’re deciding when they’re finished. Sometimes, I need to break out of that. I started doing a painting of Ruth, my wife, just to change it up, and I realized how hard it is to observe what makes somebody look like them. You know, what is the look in their eye? It became obvious quickly how there’s no hiding place.

The paintings in the show are portraits and the accompanying music was recorded on a 4-track. In terms of mediums, these are about as old school as you can get. As an artist, how do you feel about our overly filtered, heavily auto-tuned, AI world? Do you find those tools useful at all in your work, or are they a hindrance?

I was doing stuff with Pro Tools 20 years ago. It is great. But yeah, because I was doing the paintings and it was, like you say, old school and [there’s] no hiding place, I thought it’d be interesting to break out the 4-track cassette and have no hiding place with that, as well. I was just plugging straight into the machine, and it was recording whatever I was doing without any reverb. It’s really raw, and if you don’t perform it, it doesn’t sound good. So I thought it’s a bit of a challenge, in the same way that the portraits were a bit of a challenge. Honestly, I’m more excited about this stuff than I have been for anything since probably the ‘90s.

When we first did a record and we moved to London, this is like ‘93, we did a seven-inch single. John Peel, the BBC DJ, was the guy [who], if he picked up on your stuff, he gave you a leg up. We made this seven-inch, one song on each side, and he started playing it on his show on BBC. It was recorded on an 8-track. It didn’t sound great, but it enabled us to get the music out to however many people. I just wanted to rekindle that feeling.

Do you paint and make music every day?

At the moment, I’m painting a lot because I’m building up towards this show, trying to get everything done. I treat it like a job, really. It’s five, six days a week of painting. The music goes more in and out. It’s a bit more of a love-hate relationship. I feel like I’m always going to make paintings all the time. It’s naturally what I do. But with the music, sometimes I really hate it. I’m sick of the sound of my own voice, or I want to sound like somebody else, so I just don’t do it. For the last few years, I haven’t done a lot of it. But I realized the secret to it for me is writing in a notebook every day, just writing down ideas or random lyrics, even if they don’t mean anything. I started doing that in October of last year, and I found that by amassing these words, it would make me want to pick up guitar and play two chords or something. Then all of a sudden, I start looking at the book, and I’m like, well, these words fall nicely with that. So, the secret for me to making music is to write the words first, and the guitar comes in at some point. The words kind of morph and change, but that’s how it starts off.

In thinking specifically about this upcoming show and the accompanying album, were there any artists, albums, or artistic works that you found yourself drawn to for inspiration?

With music, I’m stuck in my own little era. I do listen to new stuff every now and again, but I’ve got my favorites. I listen to Silver Jews, David Berman’s stuff, a lot. And I listen to David Bowie all the time. But I suppose with the paintings, what happened is I painted Ruth, I painted myself, and I painted my daughter, and then I was like, I need to start reaching out to people and see if they want to be subjects. And it’s amazing, actually. It’s a little experiment—you think about all the people you know and go, “Who do I think would actually like to do this?” And I’ve been spot-on every time. It’s like certain personalities that you feel, I think they’re going to want to be painted.

Once we established that it’s going to happen, I found that it was useful to find a painting from the past, just sift through stuff with books or online, until I found a pose that I felt would be good for the person I was about to paint. I did a painting, “The Artist Stag,” of my old studio mate, Sean Taggart. He’s quite dapper, so I knew I wanted him to be sitting with his clothes as part of the painting. So I looked at a Cézanne painting of the old gardener [“The Gardener Vallier”]. Well, that’s a perfect pose for Sean. And I realized that the gardener in the Cézanne painting is sitting in his garden. Then [I realized], Sean’s gotta be sitting in his studio. So I painted his paintings behind Sean. I found inspiration from all these different painters from the past. It’s really cool.

It seems like there would be added pressure to paint people that you know. Did you feel that at all?

I think the truth of this is when I carry on with this—because I plan on carrying on with it—it’s going to be interesting because, so far, I know all the [portrait subjects]. I think it’s going to be interesting when I start painting people who I don’t know. Because I don’t really find it a problem to paint somebody sitting there in front of me who’s a friend. I mean, I feel like there’s a responsibility to create something that they’re not going to be scared out of their wits when they see it but, I don’t know. I feel like I’m starting on this path with these portraits, and I don’t really know where it’s going to go. I find it really interesting, what makes somebody look like [them].

You have such an impressive portfolio of work. Is there anything that, as an artist, you aspire to be better at?

Oof. Yeah. All of it, really. A lot of the time I don’t afford myself the luxury of thinking I’m good. I just think it’s inevitable that I’m going to get better. It’d be concerning if I start thinking the opposite. I mean, like preparing for this music show in October—I’ve not played a show for 10 years, but I feel like I’m singing better than I ever have, and that’s just because you get older and you feel more comfortable. So, I just keep chipping away. In the end, something good happens, hopefully.

Going back to this idea of a personal brand—it can be very difficult for some people to begin working in the arts because there’s this sense now that if you don’t have a platform or you’re not an instant success, it’s not worth it. Do you have any advice on how to enjoy the process and let go of that need for external validation?

I think it’s really hard to tune out that stuff. I try to keep it at arm’s length. Keep doing [the work] all the time. I teach a class at a local gallery once a week. I was talking to one of the ladies who does the class, and she was like, “I feel like I’ve reached this plateau with what I’m doing. Have [you] got any advice?” We were looking at her sketches. She’d just been to Maine, and she was doing some sketches of the ocean. She’s pretty good, and I just found myself going, “I don’t know if I have advice. I think that you’re on decent track. Just make time to do more of it, and maybe isolate what it is you’re trying to do.”

Like how I’m spending this year just doing portraits. I want to get better at this one thing and I’m going to spend six months or a year doing it. And make sure, during that period of time, you work at it every day. I mean, it’s the same with everything. I don’t think art is any different to anything else. It’s like training for a bike race. It’s the same thing. If I don’t train on my bike a lot, it’s never going to work.

What do you hope that people will get from seeing the work in Professional Human?

Hopefully the paintings will say something to the viewer, and then I don’t have to say anything. [Laughs] In the past, with more abstract paintings, people will look at them and I feel like I’m trying to justify them to people, whereas with these paintings, they’re very simple. They’re a person, and they’re looking straight back at you, the viewer. I think if I’ve done my job well, then hopefully people will feel that when they see the paintings. If they come out of it thinking that I’m a good painter, then I’ll be really happy.

Now that this exhibit is about to open, what’s next for you?

I know I’m going to carry on doing portraits, but I also know myself, and I think I’m going to want to do something different, as well. I don’t see why I can’t carry on doing portraits, landscape paintings, abstract paintings when I want, you know? People quite often say, “You do lots of different things,” but I’ve always perceived it as a problem. It’s not an easy sell. But I’m finally embracing the fact that maybe it’s good doing lots of different things. Maybe I’ll go back to doing the wire paintings. I don’t know what I’m going to do. Now that I’m saying it, I’m quite excited.

To learn more about TB Ward, visit his website.

To find details on Professional Human, visit Upstream Gallery.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…