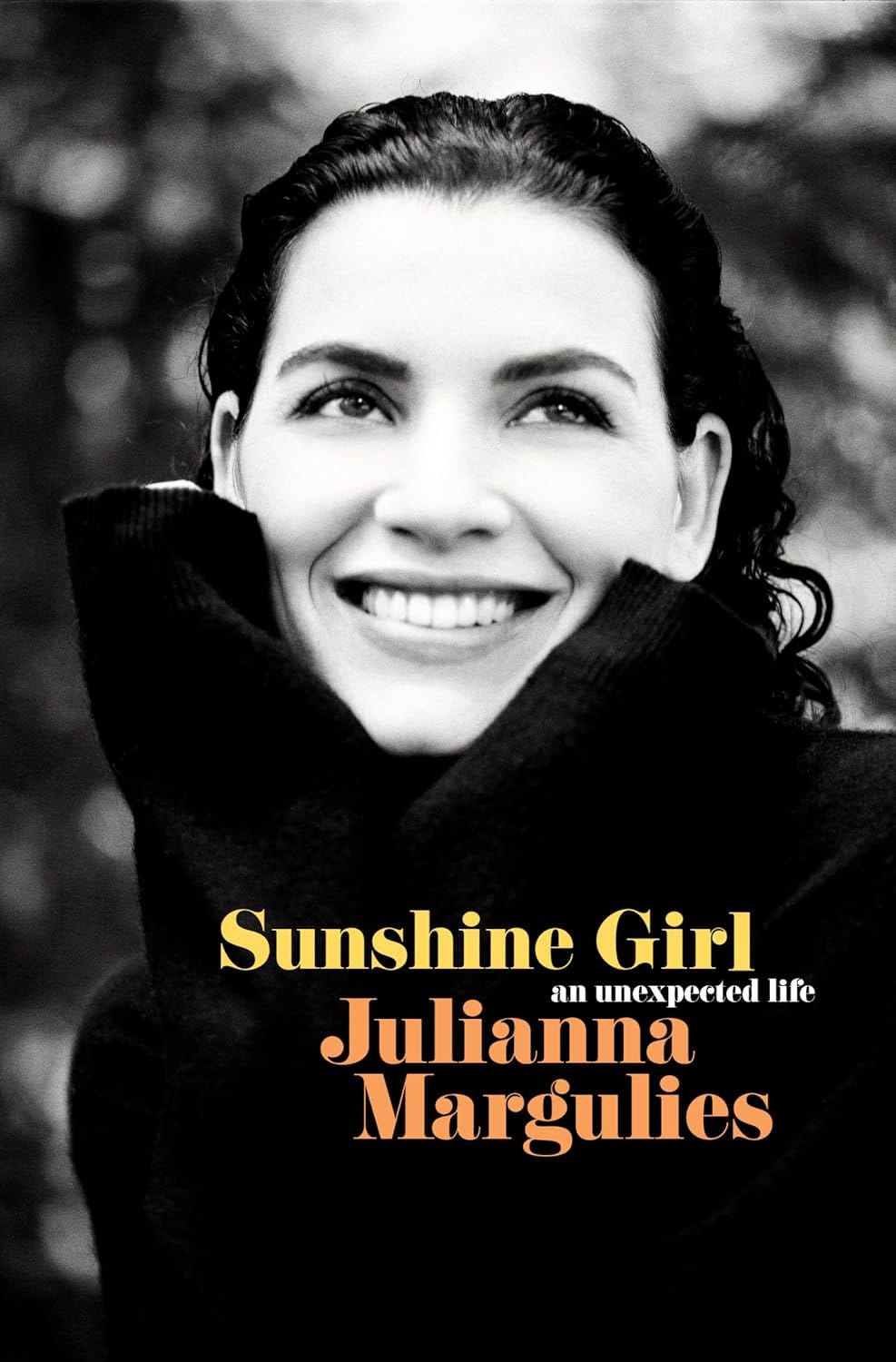

That Time Julianna Margulies Opened Up About Being the ‘Sunshine Girl’

Tidbits from the archive.

Four years ago this week, Shondaland published my interview with actress Julianna Margulies. It was my first major celebrity interview, and I was enormously grateful that it was with someone so kind and down to earth.

As I wrote in the intro to the original piece, as a girl, Margulies was shuttled back and forth between divorced parents living on separate continents. Her father, a successful advertising executive who wrote the Alka Seltzer “plop, plop, fizz, fizz” jingle, lived in comfort, while her mother, a free spirited former dancer who was constantly trying to find herself, could barely pay the bills. As the family’s “Sunshine Girl,” a nickname bestowed upon her by her mother, Margulies took it upon herself to try to keep everyone around her happy. It’s a mindset that would go on to define much of her adult life.

Over the course of a nearly hour-long Zoom call, Margulies told me about her turbulent upbringing; her traumatic encounters with Steven Seagal, Russell Simmons, and Harvey Weinstein; and how her role in The Good Wife inspired her to write her memoir, Sunshine Girl. Due to space limitations, much of our conversation did not make it into print. So, in honor of this week’s fourth anniversary of the interview, I’m sharing the outtakes.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: Congratulations on your book! I’ve been aware of your work for a long time but didn’t know anything about your upbringing. Was it daunting to put such personal information out there?

JULIANNA MARGULIES: Yes. I have to say thanks to my editor, who would push me sometimes. I would say, “No, no, no. I’m not a public person.” And she’d say, “Sit with it for a few days and see what you come up with.” And then I would start to write, and I’d say, “You know what? I actually need to write this.”

I wanted this to be a coming-of-age story. And I felt confident because I had my mother’s blessing. I always said, “I have to wait until my mother dies before I can write a book about my life.” Because she was such a central part of it, but also such an eccentric character. But the truth is, not only did she give me her blessing, but she gave me the freedom to write everything. She never once said, “Oh, please don’t write that.” She owns her stuff.

The hard part growing up with a mother who was so self-obsessed about finding herself, to the point where she would forget about the needs of her children, is that she has never stopped searching. Even in her eighties now, she’s reading Thich Nhat Hanh, she’s meditating. She’s always searching to improve her life. And with that comes absolute and total acceptance of who she was. That freedom allowed me room to write everything down that I remembered as a child. I kept journals since I was nine and that was really helpful.

I’ve kept a journal since I was nine, as well. They’re mortifying to read now. But I would imagine they were useful.

Yeah. It’s what worries me about computers now. I wonder if kids who were our age then are journaling? That was my sacred time at night. I would write in my journal before I went to sleep. And to keep track of your life, it’s a really special thing. It takes discipline to do it. It was invaluable for me to have them, for sure.

You delve into a lot about your childhood. I barely remember three weeks ago, let alone decades ago. Were your sisters and your mom helpful in filling in the gaps as you were trying to recall details?

I don’t remember what I did three weeks ago, either. But because my childhood was quite traumatic and dramatic in all the different moves and different countries and different schools and different boyfriends, you remember trauma and drama. You don’t remember a complacent everyday life because it’s somewhat the same every day. But when you are on an airplane at the age of 11, not really understanding where you’re going, and you arrive and your mother isn’t there to pick you up, you remember the smell of the room, you remember the creases on [the customs officer’s] face. I had enough in my own memory, plus the journals that I kept.

I had to check in with my sisters [and] my mother about things because I would lose track of which boyfriend was where. I emailed both my sisters about the story, I think it’s in the second chapter of the book, where my mother [came] home with a man who had a pet monkey. I emailed them to say, “This is what I remember, but I was only three years old, so I’m not sure if it was told to me or if it was a joke.” I wrote down my version of the story. I said, “Did this happen?” Both of them wrote back different versions of the exact same story. So I thought, “Okay, it happened. I can only write from my point of view. I can’t write from their point of view; that’s their book to write.” So that’s what I did. My mother, to this day, still says it didn’t happen. But I don’t know how three daughters all remember the exact same thing. I mean, it’s not like we made it up. Who makes that story up?

When you started delving into those memories, were there particular emotions that bubbled to the surface?

It was a gamut of emotions. Sometimes I’d write a chapter, and I would read it out loud to myself. Being the daughter of an advertising executive, he would always say, “If you can’t take a breath, it’s not a well-written sentence.” So I would read it back out loud to myself and there were times where I would start crying. When I heard it verbally, it was too hard. Writing it felt easier.

Almost every completed chapter, I’d either call my mother on the phone or I would drive to her house and read it to her. And there were always tears and laughter. I tried to bring levity to it and not just have it thump you over the head with “woe is me.” Because that’s not how I feel. I feel like this is a coming-of-age story and it took a lot of my adult life to sort through it.

I guess it’s also wanting to say, “Yes, I had parents who weren’t always present, but they guided me with such love.” Even though my mother was narcissistic and did not put my needs first, ever, at the same time, as an adult, I went, “Wait a minute, Dad. Why are you getting all the praise? You’re half of this parenting. Where were you?” What I loved about the process of writing the book was coming full circle and saying, yeah, those things happened, and I called [my parents] out on it as an adult. When they both apologized, I let it go. I dropped the baggage because I don’t want to have a toxic relationship with anyone, let alone my parents. I am so grateful that I worked all my stuff out with my dad because he died suddenly and I will never get that time back. But when he died, I had no regrets. I heard, “I’m sorry. Forgive me. I should have done more.” And I said, “You got it. Thank you.” It’s all I need.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Creative Reverberations to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.