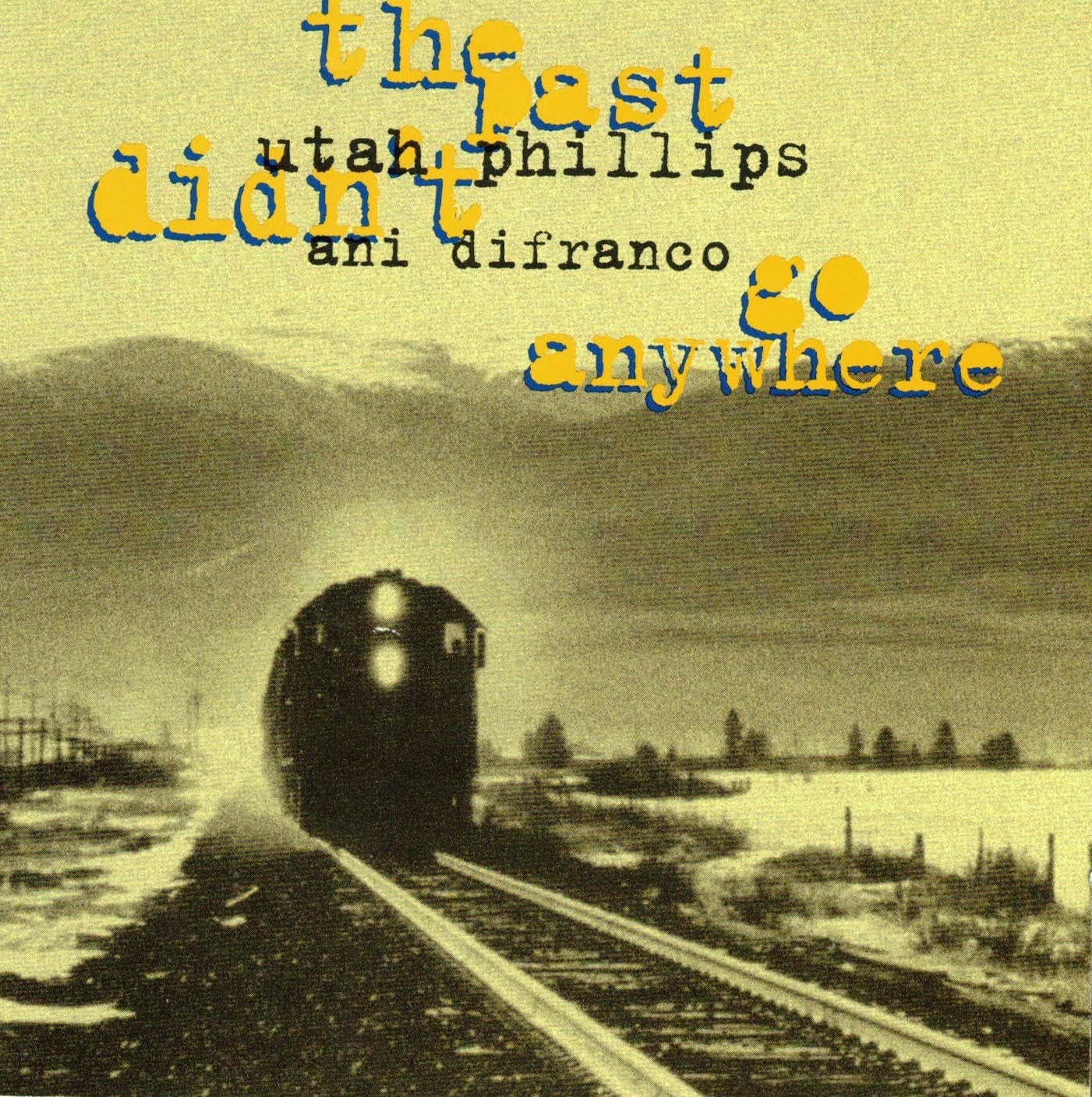

In October 2021, I had the pleasure of interviewing Ani DiFranco, an artist I’d been a fan of for decades, for the third time. The interview, conducted for AARP, was intended to be about the 25th anniversary of The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere, an album featuring the stories of folk legend Utah Phillips set to Ani’s original music. But during our 90-minute Zoom call, we covered a wide range of topics, from the making of the album to the pandemic, which was still raging, as well as new artists she was into, the concept of restorative justice, the “weird” process of adapting her memoir for the screen, and her relationship with “notable elders” in the folk music scene.

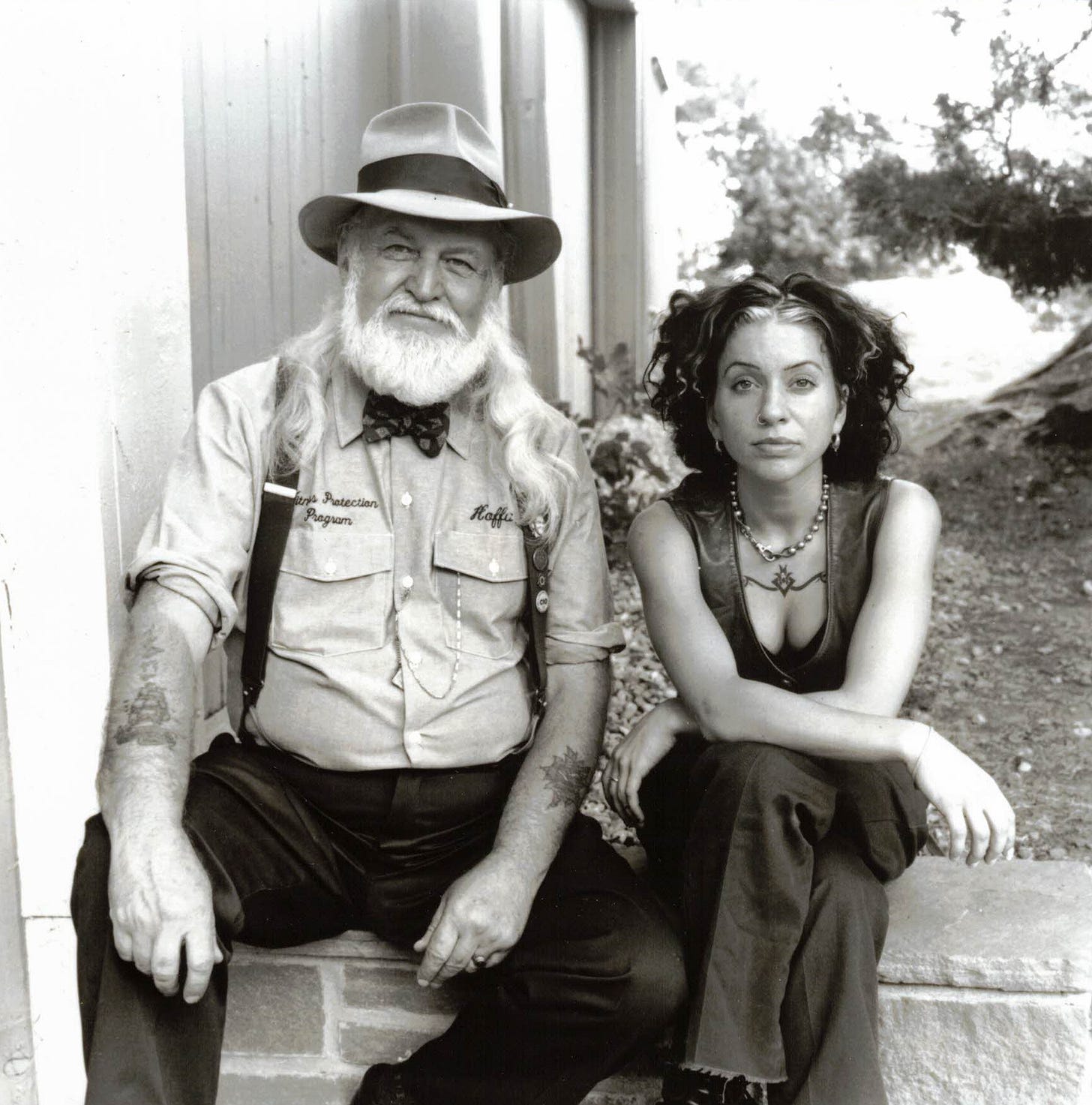

As DiFranco shared during our chat, it was Utah, who was 61 at the time of the album’s release, and others of his generation who were most supportive of her early work. “I started going to these folk festivals and I was being judged a lot by the broader folk community,” DiFranco says. “I looked different. I acted different. I sounded different. I was shaking things up and was not welcome by some of the folk traditionalists. But Utah, Pete Seeger, Tom Paxton, Si Kahn, Peter Yarrow—those were the old folk fogies I can think of off the top of my head who were just like, ‘Ah, come here, kid. You’re one of us.’ They saw themselves in me and saw in my work a continuation of their own work.”

Our interview was published as a short profile on AARP.org’s members-only website, but after a few years it was pulled due to a site redesign. I’ve been given permission by my editor there to republish the piece as a Q&A here. Much of what is included has never been published before, so I’m excited to share it with you now.

SANDRA EBEJER: How’s your year going?

ANI DIFRANCO: Good. I would say it’s an uptick from last year. How about you?

I think it’s okay? This is my third time interviewing you. The first was at the very beginning of the pandemic, when you just had come back from recording Revolutionary Love and everything was weird. Nobody knew what was going on. And then when I talked to you in January after that album’s release, it was, I think, much more of a reluctant acceptance of the pandemic. And now, I just don’t know.

I know what you’re saying. I feel much like you do, just discombobulated.

Yeah. And you just went on tour!

Yes. That was chaos. I guess we’re not going to attempt to do that for another little while. So I’m back into folk singer lockdown. But even life at home seems jumbled and confusing.

When you go on tour and everything offstage is chaos, are you able to do what you need to do on stage to perform?

That part of it was awesome, just connecting with audiences in the field. It took me about three shows, I would say. I was like, “Geez. What other skills do I have? Maybe this is just not even the thing to do anymore?” And at about show three, I was like, “Fuck yeah! I miss you guys!” And man, just seeing audiences, especially at the indoor clubs. We did some clubs and [attendees were] masked all night, singing along, steaming up their faces, getting a face full of zits. It was difficult, as anybody who spends a while in a mask [knows], but seeing people rise to it, it was very touching, given what’s happening everywhere in our society, to see a group of people take care of each other and suffer through it because that’s what you got to do.

Totally. There are those little moments, which I’m sure your audiences felt, where things feel normal again. And then they go back to not being normal. So, this interview is about The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere. I pulled out my copy that I bought right around the time it came out 25 years ago. When did you first meet Utah? Did you know of his work prior to meeting him?

Not long before meeting him I learned of his work. I think that was 1990. It was certainly by ‘92. It was when I got picked up by a national booking agent, which at that time was called Fleming Tamulevich, later just Fleming Artists. They were like the folk mafia. They were the big folk booking agent. I was making a stir on the folk scene. I had played a couple folk festivals and people noticed I was connecting with audiences, but I was totally independent. So this big, to me at the time, fancy booking agent came to check me out and ended up signing me, and Utah was another artist on their roster. Instantly, I became kindred with a lot of folk singers through Fleming, and Utah was one of them.

Your album Dilate had come out earlier in the year. That was around the time when you became more widely known. You were on MTV, you’re on all these magazine covers, and you follow up Dilate with The Past Didn’t Go Anywhere—this album of stories by this elder folk singer many people had never heard of. What inspired you to make this album at that point?

I was getting to know Utah and these other folk legends through hanging out on this scene. I was in with the in crowd. I found myself on stage with Utah a lot, [doing] political song workshops or benefits for this or that activist organization. So I was becoming very familiar with his deal. I felt like so much of the vitality of his art lived in between the songs on stage. I felt a lot of connection with the stories that he would tell, the jokes, the whole performance. It was performance art, and the songs were a part of it. And yet, the only documents are of the songs. But what he did on stage was so much more than that. I think I might have put it in the liner notes— I’m not sure. Did I? Are there liner notes?

There are.

Oh, okay. I remember saying that the songs felt almost like intermissions. There’s moments where you breathe into a little melody or reflect on what he just laid down. I felt like the essence of his art was not being documented. So I went to him with this idea of taking his stories and making an album of those. I thought it might be hard to get people to sit down and listen to an old dude rambling for the length of an album, so I would accompany his stories [with music]. And he had respect for me and had trust in my ideas. He said, “Go for it. Okay. Sure. I don’t know.” I think it was surprising what came out. And at first, for him, there was an acclimating to this sort of pseudo hip-hop, beat-laden [music]. He was like, “Whoa. The music seems kind of loud. It’s a lot for me.” But he acclimated to it, and I think he realized, “I have to trust her. This is a way for my stories to reach a younger audience.” So he went for it.

Not only are there liner notes, there are great liner notes. You have a line in there where you write, “I listened to Utah for three days at 75 miles per hour, alternately laughing, weeping, and jotting cryptic notes on napkins while swerving lane to lane.” Do you remember the drive you took to Austin to record this?

I don’t remember ingesting tapes while driving, per se, but I believe myself. What I remember is proposing the idea to Utah, him giving it the thumbs up, and then I was like, “I need whatever recordings you have of your live performances. I’m gonna mine your stories from recordings of you on stage.” Because I knew the gig was not going to be “get Utah in a recording studio alone and record him performing, talking to people as though people were there.” That was not going to cut it. He is a performer and it’s about the audience, and it’s about connecting with them. That energy is what drives the performance. I knew I needed live recordings.

So he sent me all the live recordings of himself that he had. His only copies. It was a box full of cassette tapes. He sent them through the U.S. mail, and I received the recorded history of Utah on stage in a little cardboard box. And so yeah, I was listening to those cassettes in my cassette player in my—God, what would it have been?—probably a little Hyundai at that time, driving down to Austin to make this record. The first part of the process was to take all those cassettes and digitize them for posterity, and also so that I could work with them more easily.

One of my favorite tracks on the album samples Jesse Jackson. You also sample General Douglas MacArthur. What was the decision-making process behind adding them?

I had a CD called Great Speeches of Our Time or something. I don’t know why I had this CD. I actually can’t imagine why I had this CD, or how it came to me. But I guess I was just thinking they were ironic voices to juxtapose against what Utah was laying down, so I pulled a few things off of that CD randomly. I mean, I’m a spleen-driven, instinct-following person in the studio and otherwise, so I guess it was all because that CD was in my car somewhere.

Were you nervous to share the finished tracks with Utah?

Definitely.

Did you present it to him as a fully realized album?

Yes. I put the whole thing together and then laid it on him. I don’t think I was of a mind that I should share with him the process along the way. I knew it was gonna be a lot for him to acclimate to this new context for his work and this radical presentation. So, yeah, I played it to him as a finished deal. And it took him a minute. At first he was taken aback and then he decided to give over to it.

I remember shortly thereafter being at the Folk Alliance Conference after the record had come out, and Utah was being given a Lifetime Achievement Award. There was a spotlight on him, and they put Utah’s picture up on the screen, and they say, “And now to present the Lifetime Achievement Award” and somebody comes out and they start playing that record. This super heavy beat kicks in, this heavy bass—that’s just something you’d never heard at the Folk Alliance and it’s for Utah. The whole room erupted in laughter and shock. Oh, God, it was so weird. I’m sure a lot of those folk fascists were thumbing their nose at me and my crazy record, and what did I think I was doing with Utah?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Creative Reverberations to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.