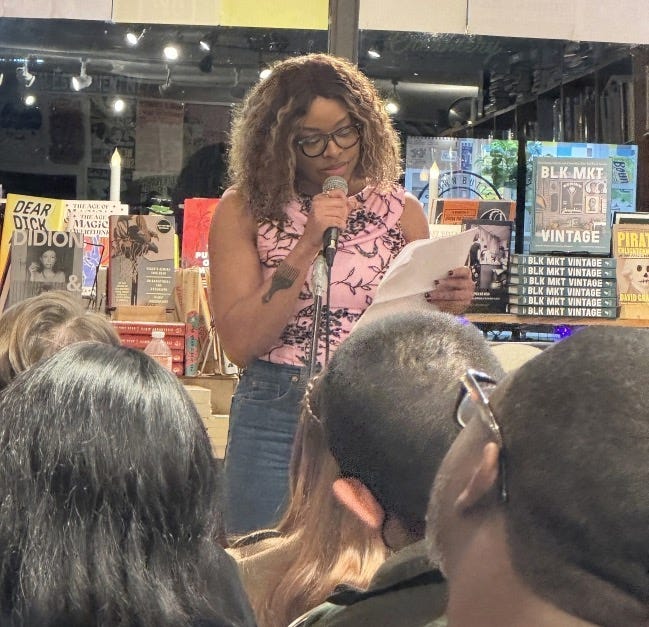

CR 031: Kindall Gant on Poetry, Creativity, and the Joy of Experimentation

The poet discusses her creative process and her passion for the arts.

In her haunting poem “time capsule,” Kindall Gant’s childhood memories of Hurricane Katrina are brought to life in vivid detail. Only seven at the time of the event, Gant writes of “traversing lake pontchartrain / for hours” as a “genocide masquerading as natural / disaster” ravages her hometown. Nominated for a prestigious Pushcart Prize, the piece was inspired by artist Howardena Pindell’s collage Autobiography: Oval Memory #1 and is just one example of Gant’s deft ability to take a favorite work of art—a painting, a photograph, a song lyric, a TV show quote, even another poem—and transform it into something entirely her own.

Gant’s poems have been published in numerous outlets, including Torch Magazine and 1619 Speaks: An Anthology of African American Poetry. When she’s not writing, she’s working full-time as a book publicist, pursuing an MFA from the New School, and serving as Editor in Chief of Arcanum, a literary journal she founded in 2020.

I recently spoke with Gant about her many influences, her advice to fellow writers, and her love for ekphrasis (the act of vividly describing a scene or work of art) in poetry.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: I’d like to start by talking about your background. When did you first begin writing?

KINDALL GANT: I got interested in writing and in poetry around middle school. It’s funny—I started writing fan fiction around Avatar. I’d write the new chapters at my summer camp when I was little. And after that, I realized I had interest in writing poems and world building and exploring what it might be like to write creatively. So that’s how it all began. Of course, it’s developed over the years. I studied writing in undergrad, I’m finishing up a grad program now, and I’ve been working on a lot of poems, which is really exciting. I’ve transitioned into writing more from the arts perspective. I write a lot of ekphrastic poems that are based on works of art, and I also have stuck to wanting to world build and wanting to envision a new future. That’s what a lot of my current work has been about.

I feel like every writer, regardless of the genre, uses their work to do more than just tell a story. They’re usually trying to find out something about themselves or work out a problem that they’re dealing with. What purpose does your work serve for you?

Well, I love art. I wasn’t exposed to it as much when I was younger, and now I’ve found myself in that role vis-à-vis working in publishing. I actually started off in publishing with art books, so I got into those, and started going to museums more frequently than I did when I was younger and living in New Orleans. Those things have melded together for me in terms of what my interests are and what I hope to share with others, which is engagement with art.

In addition to that, I write from the Black experience; I write from the queer experience. I also am writing towards storytelling as an archive of what’s happened and what’s not been so well recorded. History ties into my work, as well as community and working towards liberation. And in my poems, that is connecting with art, but that’s also being speculative and looking not only with what’s in the piece, whether it be a photograph or a film or a song, but also adding to it and expanding to what can come after, what may be beyond, or what I’m experiencing that will be something new and innovative and exciting for someone else to understand or discover or think about or question.

You mentioned growing up in New Orleans. I love your poem “time capsule,” which is about Hurricane Katrina. Can you talk about New Orleans and what role that city has played in your work?

It’s played a big role. I’m actually working on a set of poems with “time capsule” that are based on Howardena Pindell’s Autobiography series. It’s a collage series, and “time capsule” is based on Autobiography: Oval Memory, a beautiful collage piece. It’s multicolored, it has a lot of blues in it. The connection to her work, for me, is really powerful. She handles memory in a really interesting way, and sees it as something that is ever shifting, and explores that in this collage series. I feel like my poem “time capsule” parallels that. It’s about New Orleans, it’s about Katrina. It’s about the experience of growing up and having something like that happen and seeing it in real time, but also seeing it reflected in the media and the news. There’s a lot that went untold about Katrina, or a lot that’s been buried or hidden. And my work in history is to resist erasure. I wanted to tell my experience of that story that has been well circulated in some places, and not so well circulated in others.

And I played with the form, trying to illustrate the fact that memory is one of those things where, if you remember something, the next time you remember it the memory has shifted, and it’s something else. The structure also plays with that in terms of the slashes and being able to piece disparate parts of the poem that may be far away in a traditional left to right reading of it. That poem is really close to my heart in terms of speaking out and sharing something of myself, but also of my community, and shedding light on something that, quite frankly, happens very often.

Your work pulls from so many different art forms and influences. Who are some of the artists that you repeatedly turn to for inspiration?

I love everyone. [Laughs] I’ll start with Sun Ra, because I feel like Sun Ra concepted what Afrofuturism is in terms of the work that he explored, vis-à-vis his poetry, vis-à-vis his jazz music, and then also his film Space is the Place, which was a real cultural moment. But I also have more contemporary sources of inspiration, like Howardena Pindell, like Rachel Eliza Griffiths—she works in poetry and photography. Mickalene Thomas creates the most beautiful collages of black femmes and black women. They’re multi textured. She also started working on a new series, which is different but evokes the same wonder and awe and amazement at who is reflected in her work. Legacy Russell—I’m reading Black Meme right now. It’s really great. Kind of breaks everything down, and it’s something that I’m looking towards as inspiration for my thesis, which is on Afrofuturism in art and literature. Those are my main people I look to when looking for inspiration.

Tell me about your literary magazine, Arcanum. What made you decide to launch it and what are your plans for it going forward?

It’s still a work in progress, but I have a new team and we’re hoping to publish some things in February and really get the gears turning around Black History Month. It’s a project that started in 2020, during the Black Lives Matter movement. I wanted to create a space where Black creatives could showcase their work, share their experiences, but also be paid in a way that felt equitable. That’s where it began. We just put out a queer reading recommendations post to share resources. That’s something that, on social media and Instagram, we’re looking to do for Black and BIPOC creatives—to have a space to see work, see visual art, see poetry, see film criticism, and also get resources [like] where should we be submitting? What residencies are open right now?

That’s very cool. Do you write every day?

Ha! I laugh at that. In some ways, yes, I do. It’s hard. I’m trying my best. I’m in grad school, so for a certain amount of time, there were classes and homework and things I had to write in that capacity that maybe didn’t feel as oriented to what my practice is now, or what my current project is. So I say yes, in some capacity, but am I writing a poem every day? No. Not even close. But some lines—I might jot something down on the train or something might hit every day. But it’s not as consistent or as disciplined as I’d like it to be. I’m getting there.

Well, you’re so busy. In addition to grad school, you work full-time. You’ve also done many residencies and received fellowships for your work. How do you balance your work as a publicist with your creative endeavors?

The residencies and the fellowships that require leaving [New York City] I’ve had to use my paid time off for, which is something that I don’t think gets talked about often enough when you have a full-time nine-to-five and also are trying to invest in yourself and your writing and create space and time and all that. I haven’t done as many residencies and fellowships during grad school, just because the time is hard to find, so I’ve focused more on workshops. I did one earlier this year at Ma’s House, which was great, and it was close by, so it was more feasible because it was still in the state of New York. But it’s definitely a balance. Sometimes things will fall through the cracks. I would not recommend to anyone to work full time and be in grad school, but you do what you have to do.

With that MFA in mind, as you envision your career in the coming years, what do you hope for?

I hope for my book. I really do hope for my book, and I hope for it to end up in the home that is suited for it. Working in publishing gives you a different perspective, I think, on how you may want that to pan out for yourself. There are a lot of open avenues, and I want to go down the right one, for sure. And I hope for more time to enjoy life. We’re all going through it. It’s a really hard time, everywhere, all the time.

Are there any goals that you have for your writing? In other words, are there new forms of poetry or new subjects that you’d like to explore?

Yeah. I would love to do different things. I think the next book or the next set of work cannot be ekphrastic. It needs to be just my poems. Maybe some pop culture influences, maybe some references. But in terms of other goals, I’d love to try different forms. I still haven’t written a duplex. I gotta get on that. I do play with form in my current work, but there are things that I haven’t tried. And then long-term, I want to have fun with it—read a little, share a little more with my peers, my friends, and other people that I have yet to meet who may be a part of my writing community in the future.

I’ve asked this question of other writers, and I’m wondering what your thoughts are on the subject. Are poems ever done? Or do you find that they continue to evolve over time?

That’s a great question. That’s part of my problem. I keep tinkering and tinkering. I mean, they’re done when you release them into the world. There are moments where you read them afterwards and are like, “I wish I’d tweaked that” or “Oh my God. Why did I write that?” Because I feel like poems exist for that moment in time that you wrote them, and also that moment in time that you shopped them around or did whatever else you had to do with them, but your perspective of them changes, just like memory. So they’re never done, but you have to release them at some point.

What about when you do a reading of an older poem? Do you allow yourself to tweak it, so it’s published one way, but different for the reading?

Well, for all the poetry people out there, when you publish a poem in a journal or a literary magazine, you can still change it with the book. There is that. But most of the time, if they’re published, I read them as they were already. I think me releasing them and being open to having them published is a sign of me letting that poem go. I don’t tweak them much after I do that. And if I don’t like them, that’s not what I’m going to read. [Laughs]

Good point. You’ve taught workshops. What is one piece of writing advice that you find yourself giving over and over?

I’m pretty experimental in terms of what I write and also what I teach. Historically, I’ve been doing ekphrastic workshops, but I have one coming up that’s about resisting traditional structures and notions and going beyond convention, so to speak, not just in terms of the actual form of the poetry, but also in terms of the content we’re exploring. So I think the best piece of advice that I’ve given is just to try new things. Be open to doing that, even if it doesn’t work the first time. That’s how you generate work. I think that matters and is important and means something. Because if you start a poem and you already know what it’s about, then what’s the joy of writing it?

To learn more about Kindall Gant, find her on Instagram or visit her website.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You might also enjoy…

A great read Sandra,

Poems start at the heart.