CR 005: Sean Scott Hicks on Crime, Writing, and Redemption

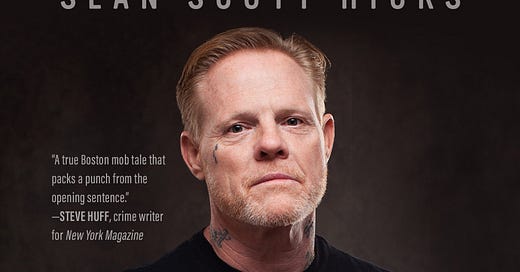

The former mafia member discusses his scintillating new memoir, "The Devil to Pay: A Mobster's Road to Perdition."

Sean Scott Hicks was born into a life of crime. His paternal uncle, Howie Winter, co-founded Boston’s infamous Irish mob, the Winter Hill Gang. His stepfather was a close friend and associate to some of the biggest criminals in the Boston area. As a child in the 1970s, Hicks listened in on business dealings made by guys like James “Whitey” Bulger (known to Hicks as “Uncle Jim”), and by age 15 he was running his own crew.

A school dropout with a fourth-grade education, Hicks was 17 when a prison optometrist mocked his inability to read. It was at that point that he decided to educate himself. “Most of the state prisons in Massachusetts have a section that’s cordoned off for inmates when their children come up,” he says. “Generally, it’s tucked away in a corner, and they’ll have activities, little plastic tables and chairs, coloring books, and children’s books. I thought that would be the easiest way for me to read.” After teaching himself the alphabet, he graduated to Dr. Seuss books, eventually earning his GED. But it was later, after he discovered Edward Bunker’s Education of a Felon while serving five years at Walpole State Prison, that he realized he might one day be able to write a book of his own. “It was a good amount of ego and bravado,” he says. “I said, ‘Hell, if he could do it, I can do it.’”

Now, Hicks is a published author, having recently released his first book, The Devil to Pay: A Mobster's Road to Perdition. With praise from Booklist and Publishers Weekly, the book is a blistering page-turner about the inner workings of Boston’s Irish mafia and an ex-con’s longing to find some semblance of peace.

It’s been four years since Hicks was last released from prison, and he now spends much of his time at home in the Berkshires with his wife, Charlene. In addition to promoting his memoir, he’s currently writing a fiction novel while also running a production company and a record label, Mob Rock Records. And though he’s happy to discuss his tumultuous past, he’s hoping for a more peaceful future. “I’m just going to focus on writing and my sobriety; just enjoy what’s left in my life. I already screwed up the first half, now I’m gonna fix the second.”

From his home in Massachusetts, Hicks chatted with me over Zoom about his time working for the mob, the emotional toll of writing a memoir, and what he hopes readers will get from his book.

This content contains affiliate links. I am an affiliate of Bookshop.org and I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

SANDRA EBEJER: What brought about this book? Why write a memoir now?

SEAN SCOTT HICKS: I had a lot of soul searching to do. A lot of people had been asking me to write something. After being asked numerous times, I had a few meetings with Brendan Deneen [of Blackstone Publishing]. I had written quite a bit in prison, a lot of fiction stuff, and everybody said the autobiography is what [readers] want first.

So I thought about it. I really had to take some stock in my life, and just say, “What have I honestly accomplished?” I’ve failed as a father. I suck at relationships. So that’s the motivating factor behind sitting down and writing the book: What have I really accomplished in life? What is the legacy I’m gonna leave? That I hurt people and was a terrible father and terrible husband? What do I want people to remember me for? Do I want people to come up to my children, my grandchildren in 20 or 30 years when I’m gone and talk about that stuff? I mean, I’m not naive or delusional. They’re going to. But I would like them to see that change is possible.

What was it like for you, emotionally, to revisit the moments in this book?

Well, I’m gonna be honest—living that lifestyle, there was nothing gratifying to me to get up and know that I had to go out and physically hurt somebody, whether it was over a dispute, or monies owed or whatever the case may have been. To cope with that I became an alcoholic, just to be able to live in my own skin. I would get up in the morning—I don’t know how many mirrors I punched, either still drunk from the night before or still drinking as the sun was rising. I didn’t like the person looking back at me. There were countless times I would scream in a drunken state into the mirror, “I fucking hate you!”

I didn’t really think the book would affect me the way it did. They wanted a 45 or 50-page outline. And Brendan said, “This is one of the best proposals I’ve ever read. I want to buy the book.” So we went through that whole legal process, and I started writing. I think by the second chapter, I’d tell my wife, “I gotta walk Loki,” my American Bulldog, and I would walk the dog up to the liquor store and buy a sleeve of whiskey. Then I would come home and hide it in the garage or in my boat in the yard. And it just progressed as I was writing; the more I was writing, the more I was reliving traumatic moments and situations and events. The sleeve turned to two sleeves, then four sleeves.

My wife was taking the garbage out of the pantry one day and she heard the nips clink together. And of course, I blamed it on somebody else. Honestly, I was only fooling myself, because my physical appearance changed. I started drinking 10 to 15 sleeves a day, where the package store had to order more just for me. Then Charlene said to me one day, “You're not fooling anybody. You’re drinking again. I just don’t like the fact that you didn’t talk to me about it and you think you’re hiding it from me.” Of course then I was like, “Well, if that's the case...” I went to the store and bought a couple of half-gallons. It turned into a two-year bender over the course of writing the book.

Are you doing okay now?

I am. We decided to move. It was too easy for me to be in the Worcester area because there was a package store right at the top of the hill, and I had friends that owned numerous restaurants that served alcohol. We decided to relocate to the Berkshires. There’s nothing around us but mountains. I got a bear that thinks he lives here, and a bunch of turkeys, rabbits, deer. It’s very peaceful. It’s good for writing. But I was still drinking because even though the book was done, my nightmares came back. I got to the point about five or six months ago where I was disgusted with myself. Because I’m like, “I wrote the book. I hope people don’t think that I’m trying to promote this lifestyle. I don’t want it to look like some badge of honor, or for people to read it and see it as being glamorous and alluring and seductive,” everything that drew me in as a teenager. I didn’t want that.

I had a situation when we were in Worcester—I went out to walk the dog and I heard someone yelling my name. I turned around and it was a teenager, probably about 16, 17. He was like, “Oh, man, you’re Sean Scott Hicks!” Automatically, on instinct, I’m like, “He's too young. I’ve never done anything with him in the past.” And then my mind shifted and I’m like, “Christ, did I do something to his father or uncle or some other family member?” He was like, “Dude, you were a mobster. Man, you shot people! You went to prison! That's so cool!” I was speechless. I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know how to answer him. I just put my head down with a slight shake and walked away. I felt physically sick. I’m like, this kid is looking up to me for that?

I’m glad you’re in a better place now. How long has it been since you got sober?

Three months now. Three months, and I’ve lost 30 pounds. I just made the choice, you know, what’s more important to me—alcohol, or my family and my health?

You’ve stated on social media that your book isn’t specifically an Irish mafia story or a Whitey Bulger story, but anytime someone talks about the Irish mafia in Boston, Whitey’s name is going to come up. What was your relationship like with him?

I had more day-to-day interactions with Toby Rust, Dave Breen, and Joe Simpson. Those guys were more on a day-to-day basis. [As a kid], my stepfather would stop by Toby’s house and I would beg him—“Pop,” I’d say, “Let me hang out with Uncle Toby today.” So everybody was an “uncle”; it was Uncle Joe, Uncle Toby. “Irish uncles,” we call it. And Jim [Bulger] would pop in.

I’m not gonna say I idolized him. I just thought that I wanted that lifestyle for a long period of time, probably until just a few years ago. I confused respect with fear. Everyone knew he was psychotic. He was an evil, evil person. I would have to be a sociopath to even be categorized [with him], because it bothered me, the things I did. It just bothered me. That’s part of why I became a raging alcoholic.

I remember when I first met Charlene when I got out [of prison]. This August it will be four years ago. We went out to eat someplace and I saw a couple of people looking at me when we went into the establishment. Then the manager came over and goes, “Hi. Are you Sean Scott Hicks?” And I was like, “Yeah.” There had been a newspaper article about something I did right after I got out. He introduced himself and said he was the manager. About 20 minutes later, another gentleman walked in and introduced himself. He was the owner. When it came time to pay the bill, the owner came over and said, “No, Sean. It’s okay. Your money’s no good here.” My wife was like, “Oh, that’s pretty cool. They recognize you.” And then I thought about it. I’m like, they don’t know that I’ve walked away [from that lifestyle]. So was it out of respect? Or was it out of fear?

Writing a book is a significant amount of work. What was the process like when you first began writing?

My first professional-level writing is called Heritage, and it’s fiction. I didn’t understand word counts. I was just writing a story. I was befriended by an author who owns an editing agency in Georgia. I sent a letter from prison and I was like, “Hi. How much to type?” Because I’m writing everything in longhand. She asked for some sample chapters and I sent them to her, and she says, “Well, I’ve never done this with someone from prison before, but there’s something in your writing, the way that you develop your characters, and your prose and your storytelling. You’re a natural writer.” So I would mail all of my writing to an attorney, he would photocopy and mail it to her, and keep the originals. And I just kept writing. Before I knew it, it turned into a six-part saga, almost 500,000 words.

I’ve been working on the next manuscript. Hopefully, it should be on the shelves next year. It’s called Dirty Money. Nothing to do with organized crime. It is set in Boston. I’m about 10 or 12 chapters into it. I just started reacquainting myself with it now that The Devil to Pay is done. I’m really into the characters and their development and storyline. I love the protagonist. My federal attorney said, “This is why you were asking me to send you all these law books in prison. Now I see what you were doing.” I’m like, “How do I write a John Grisham-type legal drama, courtroom battles with pharmaceutical companies and patents, if I don’t sound like a lawyer?” I have to sound like the protagonist. I gotta know what I’m talking about.

Do you have any advice for those who are in a rough place, maybe they’re imprisoned or they’re battling addiction, and they want to find a way out?

I always live by the understanding that you can hostage my flesh but never my mind. So even though I was behind concrete walls and steel bars, in my mind, I was free. That’s what I draw from to create, whether it’s music or fiction.

What do you want readers to get out of this book?

Redemption is possible. Anything in life, if you want it bad enough, and you’re willing to make the sacrifices and dedicate yourself to whatever that task may be, is most likely attainable.

To learn more about Sean Scott Hicks, find him on Instagram.

To purchase The Devil to Pay: A Mobster’s Road to Perdition, click here.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.